It was June 10, 1991. My older brother took the TV over for the night. He took the TV over every night. I was six years old. He was twelve. I had neither the intellectual nor emotional capacity to have taken in the entire run of Twin Peaks, but this was its grand finale, and it was expressed to me that this was a very. big. deal. My brother dimmed the lights and told me to sit down and shut up like he was a nun in Sunday school. I don’t know where our parents were, probably out at a company dinner (and slowly watching as ufology dissolved their marriage).

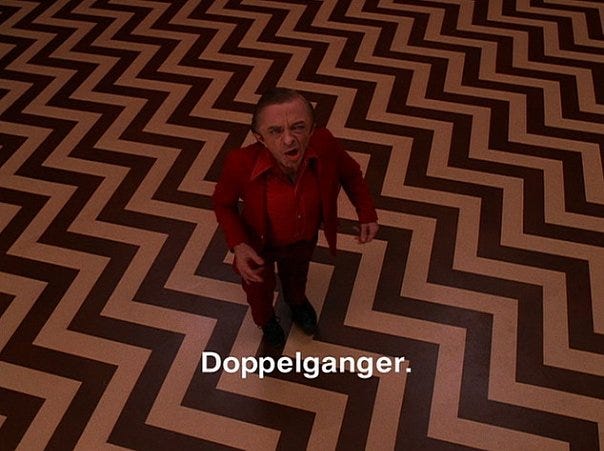

My toddler memory is spotty, but my entire world changed once Cooper entered the Black Lodge and the Man From Another Place became his guide in that bizarre space between worlds. “Wrong way!” the backward-speaking dwarf informs him, sending him to freakier and freakier rooms with screaming, white-eyed doppelgangers and dark prophecy spoken in broken fragments. Fumbling in the strobe-lit dark of the Red Room’s labyrinthine halls in his search for the kidnapped Annie Blackburn (played by a still-unknown Heather Graham), Cooper encounters his own doppelganger, who eventually overtakes him and replaces him when he returns to the real world.

Like I said, this changed me at the age of six, shook me down to my psychic core and the visions impressed on me at that time still haunt me, for good or ill.

THE NEIGHTIES (late 80s/early 90s) is the veritable doppelganger for the 80s and the 90s—grossly apparent while remaining intriguingly elusive.

Neon color—often emblematic of both decades—is on the visible light spectrum, but what about dark neon? What is it about this grainy, glow-in-the-dark time period—epitomized in my eyes by asymmetrical undercuts and bleached surfer hair over dark roots?

Lynch’s aesthetic sums it up perfectly: a bright, rosy surface over a dark, foreboding underbelly. The nostalgia for both the 80s and the 90s is all about the bright, rosy surface. The neighties embodied a darkness that is not just not talked about, but has been forgotten altogther.

Putting the two words “Dark Neon” together made sense. What I do know is the hybrid nuance of this micro-era has escaped our cultural eye. I mean “hybrid” in the sense of Homi Bhaba’s “Third Space” of ambivalent cultural hybridity—the in-between space that is both and neither.

Or, to put it another way, look at this photo of Arnold Schwarzenegger with the Crypt Keeper and tell me if it’s 80s or if it’s 90s. You can’t do it. It simply can’t be done.

The neighties were the salad days for Gen-X, who were in their 20s at the time. It was a time most millennials have no emotional attachment to or memory of. While Millennials have heavy nostalgia for Britney Spears and Blink-182, Gen-Xers by that time were well on their way into their thirties and still bummed out the Pixies broke up. There was no sense from millennials that—before the reality TV boom—the demo for MTV was for wild high school kids and the demo for VH1 was for the chill, pseudo-intellectual coffee house college crowd.

Most millennals don’t remember Kurt Cobain wearing a full ball gown on Headbanger’s Ball or when Beavis and Butt-Head first aired or what the hell Aeon Flux was. My friends at school were talking about Hey Dude and Are You Afraid of the Dark, which yes, came out in the neighties, but, along with the rest of Nickelodeon’s catalog, drips of typical 90s nostalgia. My friends weren’t allowed to watch anything outside of Rugrats. I was the exception, the adopted little brother of Gen-X, and I’d like to meet other neighties babies if you’re out there.

I can’t take credit for coining “The Neighties.” But it did come from a kid I went to summer camp with. I was 13, he was 14, and it was the summer of 1998 in the enclave of La Cañada Flintridge, a very quaint, very quiet, and very uppity suburb of L.A. (the intersection of the 2 and 210 for the Angelenos). Eric was his name, but he went by “Doog” and he spent his time drawing these unbelievably intricate comic strips. I’d sum his style up as H.R. Giger meets Clueless. We went to the Burbank mall one afternoon to see the spoof-comedy Mafia! and later, when we were shopping for CDs at Sam Goody, he laughed at me for saying Rose McGowan should date me instead of Marilyn Manson. Anyway, he maintains a criminally underrated Twitter account that catalogues remnants from the neighties. He first coined it when discussing the late 80s/early 90s with a friend and they decided to conjunct it with its own word, and rightfully so.

This has always been something I’ve been studiously aware of. It’s difficult to nail what the neighties are with words, but this newsletter is my ongoing process in figuring it out. The neighties is an era that began in 1988 and ended in 1993. Five years of crucial late-20th century culture that flies under the radar, as invisible to the undiscerning eye as ultraviolet light. I’m always annoyed by artifacts of the neighties being attributed to “The 90s” at large. And this should be said:

Nirvana is not a 90s band. It is a neighties band.

The 90s officially emerged on April 5, 1994—at the ring of that suicidal shotgun blast heard around the world. In September of that same year, Friends premiered on primetime. Boom. The 90s were born. And in 1995, the year that followed, Clueless became an instant classic (Hackers was also released for the more rambunctious among us), defining the “decade” we eventually came to know and love. A decade of bell bottoms, platform shoes, studded belts, JNCO jeans, capri pants, Motorola pagers, Green Day, spiky hair, wallet chains, boy bands, Jennifer Love Hewitt, and Britney fucking Spears.

This is not the neighties, not by a long shot.

Dawson’s Creek is a far stylistic cry from 90210. And Twin Peaks placed the neighties on an even more distant planet. 1991, I contend, was a pivotal year for the neighties, something I’ll elaborate on in future posts as I delve deeper into this darkly retro time and space, but its trajectory was undeniable in its fun, volatile chaos.

In addition to the very polarizing series finale of Twin Peaks, the summer of 1991 also saw the release of Point Break and Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey, both released within a week of each other, and both Keanu Reeves vehicles. It was this one-two punch that catapulted him into movie stardom, eventually landing him his blockbuster leading role in Speed (most certainly a 90s film).

Bill and Ted was the sister franchise to Wayne’s World, except in its pithy, platitudinal humor it managed to go to absurd metaphysical depths, something I relished in as a kid. We follow Bill and Ted as they’re murdered by evil robot versions of themselves from the future and get by on divine nonchalance traversing both the horrors and wonders of the afterlife. Bogus Journey was an ambitious sequel as far as comedies go, and among my brother’s friends, I remember it as the most anticipated sequel next to Back to the Future 3 (1990). The theater was packed.

And though the perceived banality of Bill and Ted would follow Keanu around for years (audiences not taking him seriously beyond his surfer/Valley guy visage until The Matrix), it was Point Break that proved more landmark. It was the first cool, action-packed, R-rated movie that a lot of millennials saw. Since parents most definitely forbade their kids from seeing it, a lot of my friends would come over to my house and watch the VHS. Then after we’d go to another friend’s pool and play Point Break and pretend we were the “ex-presidents,” robbing banks and going surfing.

I’ll discuss Point Break more in later posts (and Kathryn Bigelow’s ballsy early career). But in the fall of 1991 came the release of Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho, yet another Keanu vehicle, and a good place to end this first Dark Neon post. It was a movie that was made for next to nothing and a script River Phoenix’s agent refused to even show him (due largely to its homoerotic overtones). But Keanu was so stoked about the script he stuffed it in a backpack and drove on his motorcycle from New York to River Phoenix’s family home in Florida just so he could read it. River was in. The rest is indie cult/New Queer Cinema history.

I can’t even talk about River Phoenix without getting emotional. Having died in 1993 he never saw the 90s. He was a neighties icon through and through, and I’ll be honoring his memory throughout the Dark Neon landscape.

My Own Private Idaho was Van Sant’s follow-up to Drugstore Cowboy, and maintains a modern Beat poet influence, loosely adapted from Shakespeare’s Henry IV, following a narcoleptic hustler, Mike, and his hustler best friend, Scott (who’s about to inherit his father’s fortune), on a more or less self-illuminating odyssey through the streets of Portland and beyond in search of Mike’s birth mother.

Gus Van Sant certainly held a Beat current, not just in the sense that Idaho is essentially a road movie a la Kerouac’s On the Road, about the bond of two young men forged by a bohemian loyalty and unconventional love, but that Van Sant literally used the “cut-up technique” when editing the script (mixing and rearranging story fragments), which was made famous by William S. Burroughs, the Beat elder who had a cameo in Drugstore Cowboy and who himself had a nice, little neighties revival (he even showed up in a Nike commercial).

Reeves, Phoenix, Twin Peaks, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” 1991, the dark neon dimension between decades. What does it all mean? And how does it influence today? I return to the idea of the doppelganger, also known as a manufactured tulpa in the world of Twin Peaks. A tulpa in Buddhist mysticism is also known as a thoughtform, an imaginal entity that has attained its own independent lifeforce. The more I write, the deeper we’ll go, the more the neighties assumes its own identity and meaning.

Come as you are. Planet Neighties. So far out we may never come back…

![Almost Horror] Sooner or Later You Dance with the Reaper in BILL AND TED'S BOGUS JOURNEY - Nightmare on Film Street Almost Horror] Sooner or Later You Dance with the Reaper in BILL AND TED'S BOGUS JOURNEY - Nightmare on Film Street](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!iBtp!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff002c0d2-9cdd-438a-a54b-ff1d41da5588_800x439.png)